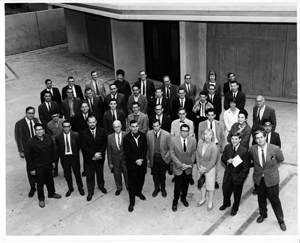

UC Santa Cruz pioneer faculty, 1965 (All photos courtesy of UC Santa Cruz Special Collections.)

UC Santa Cruz pioneer faculty, 1965 (All photos courtesy of UC Santa Cruz Special Collections.)Jean Langenheim, a Harvard-trained biologist who would go on to become a renowned plant ecologist, sat around a crackling campfire with a small group of undergraduate students.

That she was the lone female faculty member in natural sciences at the new UC Santa Cruz campus was remarkable enough. But the fact Langenheim was actually teaching a class on the ecology of redwoods, not in a classroom but beneath a starry sky and under a stand of the towering trees, was even more notable.

Jean H. Langenheim, professor of biology, at a Stevenson College faculty party in 1966.

Jean H. Langenheim, professor of biology, at a Stevenson College faculty party in 1966. “I was convinced this informal atmosphere of learning in the field and the relationships students and faculty shared there often inspired life-long environmental interests,” said the now 90-year-old Langenheim.

Todd Newberry, professor of biology, in a lab, 1966

Todd Newberry, professor of biology, in a lab, 1966It was that freedom to teach in unconventional ways and engage in research among a close-knit faculty that attracted Langenheim to the Santa Cruz campus in 1966. Many of the pioneering teachers and staff who came to UC Santa Cruz between 1964 and 1967 would be drawn by the same thing.

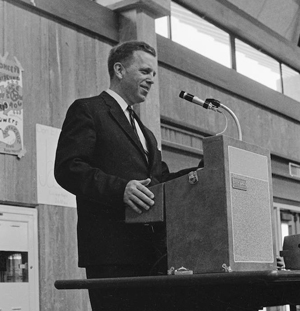

Historian Page Smith, Cowell College's first provost, with students in 1966

Historian Page Smith, Cowell College's first provost, with students in 1966Born out of the vision of then-UC President Clark Kerr and Dean McHenry, a former UCLA political science professor who was named the first chancellor of the new campus, UC Santa Cruz was to be a grand experiment in education.

Mary Holmes, professor of art history, teaching in the East Field House, ca. 1966

Mary Holmes, professor of art history, teaching in the East Field House, ca. 1966It proposed knocking down the walls of a stodgy bureaucracy, encouraging innovation, and allowing students the intimacy of a small college within a large research institution.

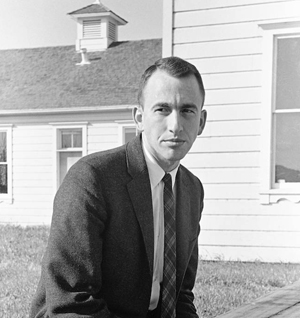

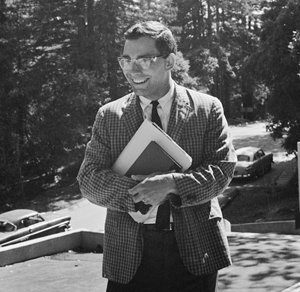

William Hitchcock, professor of history, 1966

William Hitchcock, professor of history, 1966But it was the early staff and faculty — many of which came from places like Harvard, Yale, Stanford, and even Kings College at Cambridge University — who actually carried out the plan and, in the process, established the roots of what UC Santa Cruz is today.

Byron Stookey, director of academic planning, at the Carriage House, 1966

Byron Stookey, director of academic planning, at the Carriage House, 1966“Everybody wanted to come. It was the talk of the country,” said Todd Newberry, a Stanford-trained professor of biology who arrived at the university in 1965. “How many times in your life do you get to start a university? It was going to focus on undergrads, and that’s where my heart was.”

John Dizikes, professor of history, with students, 1966

John Dizikes, professor of history, with students, 1966The campus attracted new thinkers like a horseback-riding historian from UCLA named Page Smith, the charismatic art history professor Mary Holmes, the brilliant history professor and WWII veteran William Hitchcock, and the gangly Harvard-trained Byron Stookey Jr., who would become head of academic planning for UC Santa Cruz.

G. William (Bill) Domhoff, professor of psychology, 1966

G. William (Bill) Domhoff, professor of psychology, 1966The hires were old, young, liberal, and conservative. Some came with impressive bodies of work. Other put their academic careers in jeopardy by arriving at an institution that put an emphasis on undergraduate teaching rather than on being published. They played sports with students, ate with students, invited them into their homes.

Jerry Walters, director of business services, with unidentified assistant, 1966

Jerry Walters, director of business services, with unidentified assistant, 1966“Well, of course it was exceptional and we knew it and a lot of people felt it,” said UC Santa Cruz pioneer History Professor John Dizikes in his oral history. “And (Cowell College founding Provost) Page Smith propagated overwhelmingly the idea shared by most of us, to a great degree, that we were now going to help with the reform of American higher education.”

And reform they did.

One of the first revolutionary acts of the faculty was to toss out letter grades in favor of a pass/fail system with narrative evaluations. The move was urged by Smith, who believed letter grades created a competitive situation where some students prospered at the expense of others and had no place in learning.

Or as the flamboyant pioneer Art History Professor Jasper Rose reportedly said, “Students are not vegetables. We don’t need to grade them.”

Nancy Pascal, who worked in the Registrar’s Office starting in 1966, remembered the faculty writing evaluations of students on “sticky labels, and then we’d get the labels and we’d paste them onto the right student’s records. Later the college staff would have to retype them, so there was this huge effort to support the narrative evaluation for students.”

Today, many of those who gave — and received — these narrative assessments say they were one of the best parts of UC Santa Cruz, a concrete sign that teachers were actually paying attention to students.

Besides a lack of grades, there were other indications the early faculty and staff weren’t creating your father’s university.

There were weekly “college nights,” where faculty, staff, and students sat down to a semi-formal dinner with stimulating guest speakers like beat poet Allen Ginsberg, writer/activist Susan Sontag, writer Anaïs Nin, and jazz musician Don Ellis.

There were thought-provoking college courses, which pressed against the boundaries of traditional teaching. Newberry co-taught a college course on death and another on the sense of place. Courses on building a house, on dreams, and on national identity were offered.

Harry Berger, a literature professor who came to UC Santa Cruz from Yale in 1965 and went on to become a respected literary and cultural critic, also remembered Cowell’s famous core course on world civilization. The course included seminars led, not just by humanities professors, but also, in this new world of learning, by biologists, economists, political scientists, and chemists — many who found themselves in unfamiliar territory.

“It encouraged and supported team-teaching,” Berger said of the experience. “It made it easy for people in different fields to teach together. I team-taught courses with classicists, anthropologists, and sociologists… . For me, this meant that I was not only a teacher of undergraduates but also a student of my colleagues.”

Many of the faculty and staff found themselves improvising, inventing, and tackling assignments they’d never imagined.

Pioneer professor of psychology and sociology Bill Domhoff organized a two-day, all-campus “culture break” during those first years. He brought in folklorist Alan Dundes, who gave a talk on the psychology of elephant jokes, and recruited an expert who spoke on drugs and creativity. There were talks on dreams, screenings of Ingmar Bergman movies, and construction of a fake beach, complete with lifeguard, on the East Field.

“The beauty of it turned out to be that students learned to think for themselves and to be more creative,” Domhoff said of the event he dubbed “The Fantasy Festival.”

But the times were already changing. Student protests over the Vietnam War and Civil Rights rattled the campus, and the weight of overturning old systems began to take a toll.

Faculty discovered themselves overwhelmed by the workloads of both the colleges and what were called boards of studies. Some of the campus’s brightest teachers were denied tenure because the entrenched UC advancement system didn’t take into account the new campus’s values. Political pressures mounted. Some of the old ways crept back in.

But one of the things that remained was UC Santa Cruz’s maverick spirit, an attitude that fostered improbable campus achievements like being the first to sequence the human genome, saving the endangered Peregrine falcon from extinction, finding new ways to peer more deeply into space, and helping to put organic food on American tables.

“…You walk across campus now and there are all those energetic, interested young people who are finding their way in life and learning,” said Jerry Walters, a pioneering staff member whose job included the daunting task of housing 652 students after construction delays meant they had nowhere to live. “And then, there are the discoveries and other things going on (at UC Santa Cruz) that don’t just have local impact but have national and worldwide impact.”

The man who retired as executive director of housing, dining, and childcare paused.

“Well,” he said, “it just makes me proud.”